There is a currency shortage in large parts of the country with the ATMs running dry, even before the wells could run dry this summer. Various reasons have been offered for this, but primarily this is a supply problem.

This basically means that there isn't as much currency (or cash) going around in the economy, as the economy needs.

The growth in currency in circulation is closely linked to the growth in gross domestic product (GDP, a measure of economic growth). Take a look at Figure 1, which basically plots the growth in currency in circulation along with nominal GDP growth (i.e. GDP growth which hasn't been adjusted for inflation), over a two-year period, over the years. We have taken two-year periods into account, primarily to adjust for demonetisation, which had led to a massive fall in currency in circulation.

Figure 1:

What does Figure 1 tell us? It tells us that during the two-year periods between 2012 and 2014, and 2014 and 2016, the currency in circulation grew by over 20%, as did the nominal GDP.

This changed between 2016 and 2018, when the currency in circulation grew by just 10%, whereas the nominal GDP grew by 21.7%. Hence, the growth in currency in circulation has slowed down substantially.

And this is basically what has created the shortage of currency or cash, in large parts of the country. There simply isn't enough currency or cash going around.

Let's try and estimate the gap. The currency in circulation as of March 31, 2016 was at Rs 16.63 lakh crore. This increased by 10% over a period of two years, and as of March 31, 2018, stood at 18.29 lakh crore.

But as we showed earlier, this increase is an anomaly and is too low, compared to the economic growth during the same period. Now let's say, demonetisation hadn't happened and the currency in circulation had grown at the kind of pace, as it used to before.

Let's say this growth was 25% (an average of the growth for the previous periods). At 25%, the currency in circulation as on March 31,2018, should have been around Rs 20.8 lakh crore. Of course, some part of this currency in circulation would have been replaced by digital transactions. The State Bank of India in a report points out: "The shift to digital modes could be at least Rs 1.2 lakh crore."

This basically means that the currency in circulation as of March 31, 2018, should have been at Rs 19.6 lakh crore (Rs 20.8 lakh crore - Rs 1.2 lakh crore). It is currently at Rs 18.29 lakh crore. This means a gap of around Rs 1.3 lakh crore.

If we assume a more conservative growth of 20%, then currency in circulation should have been around Rs 18.8 lakh crore, or Rs 50,000 crore more than it currently is.

While, the currency in circulation number can change depending on the assumptions we make, the broader point is that there is a shortage of currency. The government has also admitted to it. As the economic affairs secretary SC Garg put it: "We print about 500 crore of Rs 500 notes per day. We have taken steps to raise this production 5 times. In next couple of days, we'll have supply of about 2500 crore of Rs 500 notes per day. In a month, supply would be about Rs 70000-75000 crore."

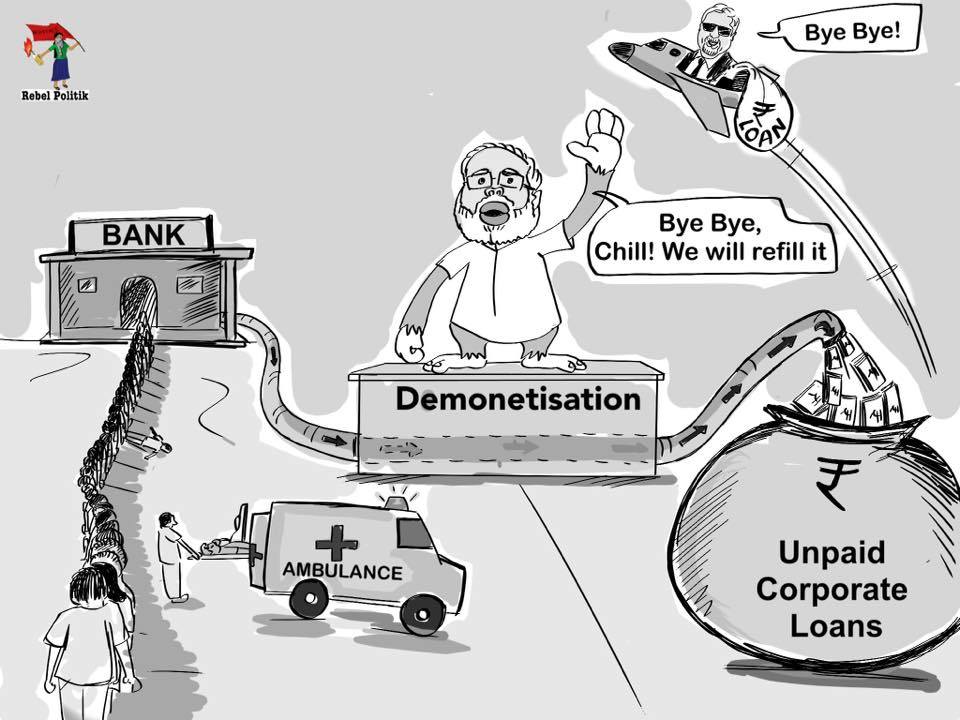

Actions speak louder than words. And this is the government admitting to the fact that there is a shortage of currency, and they are looking to increase the supply. Also, this is yet another indicator of the fact of how demonetisation cost this country dear and continues to create problems, despite its ill-effects coming down. If the Modi government hadn't demonetised Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, in November 2016, the current shortage of currency would have never happened.

Another theory being offered is that elections in Karnataka scheduled on May 12, 2018, have also played their role in the shortage. Data shows that the currency in circulation tends to increase much faster, when elections (state assemblies or Lok Sabha) are around the corner.

The trouble is that elections happen all the time, but ATMs don't run dry, as they have during April 2018. So how do we explain this situation?

In the week ending April 13, 2018, the currency in circulation has gone up by around 1.8% or Rs 33,000 crore. This is clearly on the higher side. In the past, similar jumps have happed around election time, which basically means that people (or should we say politicians) hoard on to money in order to be able to spend it before elections.

Clearly, something of that sort is happening in Karnataka as well, given the historical evidence. Past evidence also shows that such hoarding happens in the states bordering the state where elections are scheduled.

Over and above this, currency shortages have been on in a few states for a while now. Take the state of Telangana. On a recent visit to Hyderabad (in early April) we were told that the state had been facing a cash shortage for a couple of months.

In fact, MPs had even raised this question in Parliament, asking the government, if it was aware that large number of ATMs in the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, had been running out of cash. This question was answered on March 18, 2018. (Here

is the link to the government's answer).

The government in its reply said that the RBI had supplied Rs 51,523 crore to its Hyderabad office, between April 2017 and February 2018, which was the highest in the country. Clearly it wasn't enough.

The feeling we got when we were in Hyderabad was that people were generally worried about the money they had in the banks. This was aggravated by the Nirav Modi episode, which brought to the fore, the mess that public sector banks are in and all the WhatsApp rumours going around the proposed FRDI bill.

This led to people withdrawing more money from ATMs and banks than they normally would. This hoarding of cash (for both electoral as well as non-electoral reasons) obviously made the already fragile situation where the economy was generally short on cash, even more precarious. It also explains why ATMs did not run out of cash during elections previously, but have this time around.

The best way to prove this would have been to look at the total amount of cash withdrawn by people from ATMs in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar etc., where there has been a significant cash crunch. But given that state wise cash-withdrawal data is not publicly available, we will have to give this a skip.

Over the past few days as the news of cash crunch has spread, it has become what economists call a self-fulfilling prophecy. The expectation that something will happen is making it happen.

Also, as we have mentioned in the past,

the economy is finally coming outof the ill-effects of demonetisation, and this has led to greater economic activity and more demand for cash, given that most economic activity in India is carried out in cash.

Further, the Rs 2,000 note, which was introduced after demonetisation, is the preferred note of choice, when it comes to hoarding cash. The logic is simple. You can hoard more money in lesser notes. Also, the next highest denomination note now, after the Rs 2000 note, is the Rs 500 note, unlike the Rs 1,000 note earlier. And it takes four Rs 500 notes to replace a Rs 2,000 note. This accentuates the cash crunch.

All these reasons have been responsible for the shortage of currency in India. But the major reason remains the lack of supply of enough notes in the financial system.